This morning I read this post on a blog by one of my university friends. She writes from a very different background to me but that doesn’t mean we don’t find common theological ground sometimes. This morning was not one of those times. I am not suggesting she is wrong to encourage Christianity centred around love – it is the idea that there is an alternative with which I take issue.

As I read the post, I was struck by what seemed to be a very particular understanding of hell. It’s not made explicit (and doubtless she’ll be quick to correct me if I’m mistaken!) but it seemed to be a very old-fashioned point of view, laced with fire and brimstone and, to quote her illustration choice, “tortured lost souls burning forever”. It also has a certain physicality to it – the preaching she is questioning wants lost souls to avoid being sent to hell, as though three-year-old me was correct to think heaven was a place just above the sky and hell was somewhere underground. This worldview caused brief consternation on a summer holiday to Wales in the same year, when somebody asked if the hole I was digging in the sand was to get to Australia. Wouldn’t you have to dig through hell to do that? That didn’t seem like a very good idea at all. You can imagine my relief when Mum told me you couldn’t really dig to Australia, though I’m not sure at what point I realised that hell being in the way was not the precluding factor.

Intercontinental travel is no longer my primary issue with this understanding of hell, though. My biggest concern is that it doesn’t make sense in the context of everything else I understand and believe, and that was glaringly apparent to me as I read the post this morning. My main (though related) point of contention, however, was in the conditional – if love and hell work in the sort of binary opposition that is suggested, it seems if nothing else to be logically inconsistent to treat one as an experience or way of being and one as a place or at least conditions to be under. More often, we see heaven and hell held in opposition and had that been the case here I might have agreed more with the argument (though, as should become clear if it isn’t already, I still don’t think of them as physical destinations when I leave this mortal coil). The problem I have is the suggestion that a focus upon love is an a better point of departure for Christianity than a focus upon hell. To me that is devastatingly understated – love is stronger than hell because it has to be the only point of departure.

Love

As far as I’m concerned, love is the most powerful force in existence. You don’t have to look at the world from a Christian point of view to see that – there are countless examples of the extremes individuals go to when motivated by love. Sometimes we call it different things – bravery, kindness, goodness, strength – but it all boils down to love in the end. Most of us are fortunate enough to know the searing intensity of love first hand, be it shown to us or by us, in our relationships with partners, family or friends. For Christians love is the foundation of the relationship with God too. From the outside looking in that can be very difficult to understand, but just because something is different does not mean it is complicated. The clearest explanation I can think of from is a short remark a friend once made when describing his own relationship with God:

I’m His boy.

Even though I am notoriously bigandmeanandtoughandstrong I found that short sentence incredibly emotive. It’s so simple and yet intimate, and I was struck by how straightforward he made it sound. He was completely right, though.

Sometimes when I’m on my political soapbox I like to talk about the “real human impact” of policies and how important it is to think about how the theory plays out in the real world. That doesn’t mean we let emotion or sentimentality preside over reason and sense, but that we remember that politics is not just theoretical. It’s the same with theology too. Academic theology is important to me as a Catholic because, as with everything else in my life, I can only sincerely believe in something if it satisfies my head and my heart. I find myself suspicious of theologies that encourage an overly emotive foundation over reason and intellectual consistency because I think it makes a mockery of what faith means. Faith demands that we acknowledge the limitations of our capacity to know and to understand, not that we altogether dispense with reason and rationality. Similarly, philosophical arguments matter most when they have a practical impact in the real world. The challenge of belief is holding all of these ideas in balance, without overcomplicating things to the point that it loses meaning. Love challenges us similarly.

Like belief, love is at once incredibly complicated and incredibly simple. We know what love means, but how do we balance the sort of abstract love with the tangible love we might experience at any given moment? Ask me if I love my family and I’ll immediately tell you I do; ask me why and I might struggle to articulate it because here and now on a train it’s an intellectualised sort of love that governs my relationship with them. At the same time, though, there are moments when that bond feels more immediately real – that overwhelming feeling of being sad and far away from home, or those moments where pride burns in your heart, the waves of relief when somebody returns to you safely. It doesn’t mean I only love my family at those moments of intensity though – both types of love are real and both matter. I once argued fiercely with a tutor who refused to believe anybody could sincerely love a stranger because he did not think an abstract love of humanity was equally true on a specific level. I told him he was wrong and confusing possibility with difficulty and he told me I was being unrealistic. I told him that abstracts were as ‘real’ as you were prepared to make them them, and I stand by that.

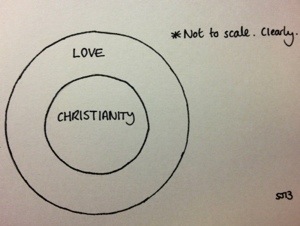

When we talk about love in a Christian sense it’s exactly the same. Love is something that we feel in our everyday life and its also a conceptual belief that governs that everyday life. Experience alone should tell us all that you don’t have to be a Christian to love or be loved, you just have to be. However, how can I say that love is fundamental to Christianity and yet say that Christianity is not fundamental to love? Easily, fortunately, and helpfully without being a massive heretic too:

Christianity teaches that God is love, which is difficult to understand in any meaningful way as long as we’re thinking of God as a bloke in the sky, or even as something somewhere. As with heaven and hell, thinking spatially makes the questioning easier but the answering harder. “God is love” just means that when we talk about God we’re talking about the truest form of love – if all of the things that we think of when we think about love are lemon-flavoured, God is a really lemony lemon. If God (in completeness) is greater than anything we can ever imagine and if God is love, then that means that love is necessarily ‘bigger’ than Christianity and also that love has to be Christianity’s point of departure. Just bog-standard, run of the mill love. The fact that love happens to tend to be extraordinary and life-changing is just incidental.

Hell

Now that we’re clear on what I mean by love, hell is a lot easier to explain. Love can operate in one direction but in a relationship it is reciprocated. If you love somebody but the feeling is unrequited it doesn’t mean that you don’t love them enough. Equally, their decision to reject you does not undermine the integrity of your love. By the same reasoning, if a person chooses not to love God that does not mean that God does not love them or tell us anything about the strength or integrity of God’s love. Just as your friend might tell you that the object of your affection is missing out by not wanting to be in a loving relationship with you, I believe that I would be missing out if I didn’t choose to be in a relationship with God. Whilst it would not change what I am or where I am, it would make my life very different. That state of being is what hell means – it is not where you are, but how you are.

Given my background, you might be surprised by that idea. However, though Catholicism has a reputation for promulgating a particularly fierce doctrine of hell, that does not mean that hell is to be understood literally. The Church also teaches that hell is to be understood as a state of being. The Catechism states:

We cannot be united with God unless we freely choose to love him. But we cannot love God if we sin gravely against him, against our neighbor or against ourselves […] To die in mortal sin without repenting and accepting God’s merciful love means remaining separated from him for ever by our own free choice. This state of definitive self-exclusion from communion with God and the blessed is called “hell”.

There are those who will have recoiled as soon as I even came close to suggesting the word ‘metaphor’ but it does not meanthat hell should be taken any less seriously. If someone tells you they are “in a dark place” you do not worry about them less if they are not shut in a wardrobe. Not believing in a literal place with literal fire does not make hell a less fearsome prospect. The only respite we have in life is the knowledge that everything is temporary. The choices we make, be it whether or not to have a slice of toast or whether or not to have a relationship with God, are not forever. We make the choice and we live by it, and if that means I’m hungry by 11am, I just have to face the consequences and remember to have a piece tomorrow. Life is temporary too, though, and if I get hit by a bus and killed on my way home, suddenly I can never have a piece of toast again. Admittedly that would be the least of my worries (I can’t actually eat bread anyway so it’s a weak analogy) but you see my point – we never know when a choice will become irreversible. The way in which I understand God and love means that my life would be worse without them. Even though sometimes other options seem more appealing, I know it’s not what I want in the long term. To be without them for eternity would be a hell that is worse than I can imagine, colloquially and literally.

Love vs Hell

All of this is why I disagree with the original post. It’s not the sentiment I disagree with – as I’ve said, I think if anything it understates how central love is to Christianity. The problem I have is with ideas of hell (and indeed sin and judgement) that are formed independently from the understanding of love, because, all else aside, I don’t see that they can ever make sense. Certain branches of Christianity spend a lot of time and spill a lot of ink worrying about how to convince people that the “Good News” is really good, and not enough time worrying about the consistency of their theology. If you put any proposition to me and ask me to believe it, I’m going to be less concerned with how nice it sounds and more worried about whether or not it makes sense. As a Christian, you presumably believe the news is good, so I struggle to understand why it needs to be dressed up to make it appeal to others. Real conviction and real relationships aren’t based on rose-tinted glasses and that’s as important to remember wherever you stand in terms of Christianity.

In life, it’s okay to fear hell, be that toastlessness or Godlessness. In fact it’s pretty sensible, far more so than avoiding thinking about it or talking about it because it doesn’t sound appealing. Equally though, there are far more powerful and constructive influences than scaremongering. If you ever need a starting point for anything, love is stronger than hell.